about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

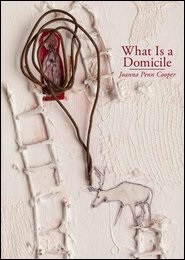

A Review of What Is a Domicile

by Joanna Penn Cooper

Spencer Dew

1

“I’m doing some dishes that have been sitting in the right side of the sink for a while,” Cooper writes, a dispatch of the everyday, the domestic:

Around here, all that happens is I wait until four to nap and then have to listen to the family below get home and clomp around like a drunk fourteen-year-old in a tube top and clogs. A whole family made up of multiple copies of the same drunk girl and her sad feathered hair.

In poems that offer fresh echoes of Ted Berrigan, alternately goofy and ebullient, quickly serious and seriously intimate, Cooper speaks of childbirth and shopping lists, the ingredients for rice salad and the process of writing poetry, bus rides and being in love, of inhabiting a self and reflecting in wonder on such selfhood: “If only I could realize it,” one voice thinks, contemplating a photograph of childhood, “Be just the person I just am.”

2

I read something once, back in college, and as I recall I read it in two contexts. In the first, in a class on writing taught by a man, a course structured around a sort of heroic ideal and veined with resentment, it read as a whine, this interview with Raymond Carver in which Carver said he wrote short stories because he had children, blaming his form on his domestic responsibilities, as if he’d have been a sprawling Russian novelist if he’d just used protection or avoided divorce. In the second context, a class on feminist poetics, this all meant something else. If we cannot go chasing bulls in order to structure our art around our own adventures, then how does life—the day-to-day of it, generally sans goring and without too many explosions—structure our art?

This is a question Cooper explores—has to explore, compelled by her inquisitiveness if not her circumstances, compelled by a poetics that, like Berrigan’s, pays attention to minutia and minute transcendences. We see, in these pages, that merely cataloguing certain details leads to those details assuming oracular form (“Awake: Dread of small tasks. Resentment.”) and that the strongest thing to say is often, counterintuitively, a statement merely about the intention to speak, or a lament about the eloquence of such speak, or a record of the construction of discourse interrupted by something necessarily and unspeakably more. “I’ve cleaned off a space on my desk big enough to riff / on you twenty times,” one poem begins, while another states that “I should put more beautiful words to this” and in another the narrator tells us “I had something else to say about this, but the baby woke up smiling and waving his arms about....” The banal opens to something broader (“a sense of the world inhabiting itself, / a sense of spaces between”) and one’s breath is taken away, not by some exotic spectacle, but by the sublime intersecting the everyday.

3

Let other men chase tornados or the piercing and/or rupture of their bodies, slavishly pacing out the script of Odysseus in the hopes of crafting a song that will make blood pressures spike. There is such beauty in the near-at-hand, here at the local branch library, here on this shared tabletop, “A structure in which to reside. An atmosphere both fluid and contained, which grounds and fades the ghosts.” And, besides, what is done best in some of those heroic novels is what is done best—and maybe better—here, in less space. One numbered section of a poem about the birth of a child says, in its entirety, “I skipped some parts.” To achieve such seeming simplicity takes a great deal of skill and work, what Cooper describes as a process of “expand and contract, expand and contract.” An economy of communication, as, for instance, in this whittled-down description, wherein we are introduced in an instant to vast information about a person’s character, mindset, and reality: “He knows I’m always trying to start conversations about shadow animals when people are trying to say goodnight.”

4

I found myself, reading and reflecting on this book, thinking comparatively: those on the tents on the beach at Troy against those back home, working the loom, weaving domestic scenes. I am sure the one half has become abstract, those journeys and muscular high jinx. I am sure my thinking on this book, my feelings for it, have been informed by the fact that during said thinking I, too, was often at the sink, or was taking instructions from a small child, or was packing the soup for the freezer, or was smoothing a bag over my hand to collect what the dog was leaving behind—a slew, in short, of domestic scenes, setting, certainly, the pace and limits and, yes, form of my existence and my understanding and ability to speak thereof. Which sounds, as I type it now, in a rare stretch of solitude, excessive, as if something in the pared economy of the domestic renders some musings not so much obsolete as simply bloated, as if there are two types of meanderings: what some have called a masculine mode and a feminine mode, but which might better be described in terms of away and home. There is the road trip, laced with epiphanies, and there is the revelation at the changing table; there is the pace and stretch of the highway, and there is that intricate compactness of the sponge. There is the mystery of the unknown and the desire to go forth and conquer it, and there is the awe-inspiring incomprehensibility of that which is at the same time so very well known. In one, the artist springs to action; in the other, the artist is repeatedly sprung by new angles of awareness within circumstance. Cooper (like Berrigan before her), is giving witness to and tracing the form of a domesticity, eyeballs and a heart here in our same, seasonal world, speaking to us, of and with and in celebration of the same “constraints” Carver lamented, speaking a bit, then stacking the dishes, but with the realization that the stacking of dishes is not marginal to but at the core of what this is, or what needs to be spoken, or “all that happens.”

Cooper puts it better, of course:

My life is not a plastic hamster ball. My life is not that refugee song.

Not any more than anyone else’s. I’ve cured myself of being

so meta, or else I’ve embraced it. Either way I’m wearing

the crown. Either way, we’re all wearing the crown.

Official Joanna Penn Cooper Web Site

Official Noctuary Press Web Site