about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

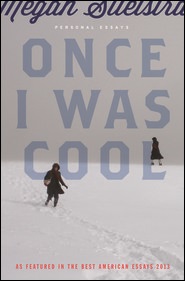

A Review of Once I Was Cool

by Megan Stielstra

Spencer Dew

...for me, fiction is truth. I haven’t yet lived enough, read enough, or dealt with enough writers in bars to be able to explain how a story—when it’s done right—can help you find yourself in others, share realities that can’t possibly be real, and show a person or people a world that you never before imagined.

No one reading decomP right now is likely to be struck by the radical newness of such a notion, and at least three of you have already stopped reading this review. But Stielstra’s insistence here is part of a larger experience of embodying familiar conceits, taking the known—or what we think is known—and parsing it out in the first person. Fiction expresses truth, art can help build a better world, parenting is an exhausting joy, and we gain perspective—even wisdom—with age and experience. There are some frightening aspects of the world, but, ultimately, we are not alone—look, I am even in communication with someone right now, reaching out, as it were, through the page. These are some themes. Stielstra tackles them in turn. Her essays are, to be sure, tales of privilege from the first world, but relatable. Honest decomP readers will likely nod along to reflections on relationships with movie characters and music houses, the ubiquitous terror of child-rearing, the reliance on eventual adulthood as an excuse for all manner of denial and milquetoast-bad behavior. Those of you with mortgages might understand the mortgage stuff; those without children will at least be able to understand that, as much as you want to write for two hours a day, sometimes even you find that you must nap or watch Netflix. Most of you, being writers, will recognize something of your own experience in the essays reflecting on the process of writing, the effects of writing, on teaching writing (most of you probably teach or want to teach, now and then, to pay those bills, possibly even that mortgage), and whether you appreciate the tone or not you’re likely to acknowledge that variety is, in fact, a good and that a full and rewarding life, however exhausting, is still, in Stielstra’s phrase “a fucking gift.”

In that phrase I read more than a whiff of speaking-into-being. Declaring the hectic jumble of one’s schedule to be “a fucking gift” here is an exertion of will as much as it is a reminder of blessings. Stielstra knows she’s lucky—there are hints here of how bad the world can be, slashed by moments of physical violence as well as the constant violence of unequal access to resources. In a society where people are struggling to express their horror, fear, rage, yet ardent hope as they continue to struggle for the most basic elements of justice—where people are fighting just to breathe, it can be easy to dismiss teacherly platitudes or well-worn modernist musings. Stielstra seems aware of this; she shrugs through certain sections, aware that you’re either with her or not, aware that, for instance, the wonder in the quote below is either something you share and are in something like shock over, still, or something for which you lack both empathy and, due to that, patience:

I built a human being from scratch. He was healthy, and awesome, and hungry. It wasn’t possible for me to fully reflect on a possible spiritual awakening brought on by the miracle of giving birth! I was a 24-hour bottomless buffet! There wasn’t room for thinking. I fed my kid. I slept. On a good day, I made the bed.

So maybe another three people stopped reading. I am pretty sure Stielstra is fine with that rate of retention. When she’s at her best she’s like one of two things, toggling between a sleight of hand magician skilled at close work (cards, the necklace borrowed from the crowd, stuff so subtle that sometimes it just seems boring for a stretch) and a motivational speaker (which is an even more fraught profession, one that really requires buy-in at the get-go; the strongest charisma in the world isn’t going to elicit an amen for that “fucking gift” line unless the audience is pretty much of that persuasion already).

Stielstra is teacherly and what should probably be called young-parental: she wants to encourage, and she’s pretty blown away by her present circumstances and how she managed, more or less accidentally, to end up here. I’m inclined to see myself described by both terms as well, so I’m, admittedly, in the audience Stielstra wants, or the audience she knows she’s not going to lose. What “teacherly” and “young-parental” most certainly are not, for instance, are “Kafkaesque,” something Stielstra also full well knows, as she knows a few things about Kafka. In an essay in which he figures, she waxes real young-parental even in a child-free moment. She’s in Prague, an American writer abroad teaching similarly displaced American students about Kafka, and she searches for coconuts, which isn’t easy, but once she gets some she has to then figure out how to open them up. So here is our narrator throwing “coconuts to the ground, four stories below, trying to crack them open. We were making gumbo from a recipe we got off the internet; for some reason, it called for coconuts.” The second sentence there pulls the first along; that final clause is the reveal. Her sleeves were rolled up the whole time, but, look, it’s your card! Ladies and gentlemen, to get the tricks, look closely.

In the teacherly mode, Stielstra wants to be useful. On this front, in my mind, footnote two to the story, “The Domino Effect” is worth the price of the book—both in terms of content (it’s a bibliography, partially, a reading list) and ethic (it’s an expression of gratitude and testament to community; it’s that whole thing about realizing you’re not alone and letting others realize they’re not alone and, honestly, these two small-print pages are as powerful as Stielstra’s powerful baby-monitor essay on the same theme). Many of these essays have something of the classroom still in and about them (traces of that communal revision, recognition of their own function as teaching tools), but the most teacherly moments aren’t those explicitly anticipating that “my students might be reading this” but those that take the young-parental bafflement at having gotten somewhere safely, having figured something out, and then, with some sleight of hand, offer what passes as wisdom on to the reader. As with the opening quote, it may be nothing new. But neither, Stielstra might well counter, are babies. Yet there’s plenty of fresh wonder just in picking them up and smelling them, again and again. In an essay about the relation between experience and art, about how to research for a piece of writing, Stielstra comes to the not-at-all-new conclusion that, ultimately, you need to do the fucking writing. Live it or Google it, just don’t defer. That’s teacherly, that’s young parental. The two ought to be (I think this is Stielstra’s stance as well as my own) intimately related. When teaching is no longer about, also, some sense of awe at the encounter with the student, their encounter with the ideas and their way of thinking, then you’re doing it wrong. Again, I likely just lost three readers, even so near the end. But buy the ticket if you want this ride; you won’t be seduced, you won’t be haunted, but you will be warmly inspired, given a firm nudge and a reassuring smile:

When I get mad because somebody parked in my parking spot, he says, “Mommy, you have to share.” He says, “Mommy? My body needs to run now. Can we go somewhere for this?” He says, “My body is full of bones and meat and mus-kulls.” He says, “Mommy Ramen-animal” for Mayor Rahm Emanuel. He says, “Will you be my friend? Friends are super cool.” He says, “Can we listen to that M.I.A. song? M.I.A. shakes my butt.” He says, “You’re the best Mommy I’ve ever had in my whole life ever,” and a thousand other amazing things, a thousand times a day. For him, I want to be a better human being, a better writer, teacher, wife, and friend. For him, I want the world to be a better place. I think art can help make that happen. And someday—two decades into the future when he’s finding himself as an adult—I want him to read my stories and be proud of me.

“Which means that now,” Stielstra writes, “I need to get to work.”

Nothing new to that last line, really. But that doesn’t make it any less of a fucking gift.

Official Megan Stielstra Web Site

Official Curbside Splendor Publishing Web Site