about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

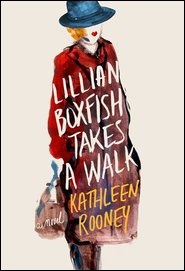

A Review of Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk

by Kathleen Rooney

Spencer Dew

What is the city to the self who lives—really lives, eyes open, on the streets—within it? More than a thinking device, more than a frame of subjectivity or an optics, an ethics, it becomes a kind of horizon, a referent and limit at once visible yet always out of the reach of articulation. Which sure doesn’t mean that those open-eyed city-folk don’t talk about it, going on and on about its serendipitous juxtapositions, those moments that are uncanny with some sense of a transcendence, as if beneath the sidewalk there really were some plan, some knowledge.

Studies of cities spring up—less academic than amateur detective in genre—those possessed by such experiences scribblings notes, scotch-taping together portfolios, cabinets of curiosity on the page: Lunch Poems or Paris Peasant, Harlem Is Nowhere or Open City.

Rooney, here, uses the story—the fantastic one, thanks to archival research—of Margaret Fishback, city-person and poet, plus the “highest-paid female advertising copywriter in the world during the 1930s, thanks to her brilliant work for R.H. Macy’s,” as raw material for a book about flânerie, a stance as much of a practice, not just walking in cities but being open to encounter, a receptivity to that which the city seems so insistently to be saying.

Lillian Boxfish, Rooney’s fictional creation, has “always cultivated a magpie mind” and uses city walks to facilitate “sideways” thinking, specifically for the purposes of composing verse and advertisements, allowing the city to help her collage together images and ideas, to innovate and see anew. In this book, she wanders both across the city and through her past, reflecting on her career, her love life, on the mechanics and joys of advertising, while experiencing the city not only as a palimpsest of that past but also always a series of new encounters. Sitting briefly with strangers, fellow New Yorkers, she is struck by how “our stories emphasize the serendipitous, even the magical. Our tone is that of conspirators, as though we are afraid to be overheard speaking fondly of a city that conventional wisdom declares beyond hope. “My long walks, I discover, have provided a rich reserve of encounters with odd, enthusiastic, decent people; I hadn’t realized that I have these stories until someone asked to hear them.” The book, of course, is one such story, or an anthology of them, arranged around a central plot.

While Boxfish is quick to say that her “long walk” is not “an accidental mock-heroic,” I am not sure what name exists (if one does) for the particular mode that this walk and its chronicling represents. Eschewing the “heroic” mode of the lone actor on a quest characterized by conflict and exertion of selfhood, the flânerie novel traces the transformation of an individual who drifts along, encountering, through the city and others, herself. Rather than a model wherein the self achieves victory, taking the treasure, defeating the dragon, Rooney gives us a narrative in which the self gets gift after gift from her attitude of engagement with the city. At times, there is an almost mystical connection of self to city. Which is not to say that there are not risks, real dangers, but that even these are subverted by the approach that is flânerie.

The “heroic” mode, viewing life as a battle, undergirds the condescension of those suburbanites who insist that those who approach city-living as something more than a phase or a misfortune will eventually wise-up and recognize their folly. But Rooney here shows that this quickness to categorize the flâneuse as naïve is itself another attitude toward the world. We can look at the world like a suburbanite, becoming a suburbanite, or we can look at the world like a flâneuse, and, in so doing, we face ourselves in a way that the suburbanite (and this is a kind of shorthand, of course) blinds herself to herself.

To borrow a metaphor from Boxfish, the city—in flânerie, in that practice, that posture, that, perhaps, faith—functions as a kind of mirror. Through being in the city we come to see ourselves, are “forced to reckon with yourself as a thing that takes up space in the world, that others can see and react to, that has a story with a beginning, middle, and end that intersects with other people’s stories.” Does that make the self something other than a hero? Freed from the myth of egotistical heroism, one recognizes oneself as a character. Flânerie decenters the self, yet presents such decentering as a profound gift. At the end of this impressive text, Boxfish isn’t merely in or of the street, she is “street” in the sense of that ingenious adjective. If flânerie offers a study of cities, it is always a study of relation—between past and present, between dreams and realities, between human beings living in a human world, neither monsters nor heroes, villains nor saints, but something still more spectacular and surprising.

Official Kathleen Rooney Web Site

Official St. Martin’s Press Web Site