about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

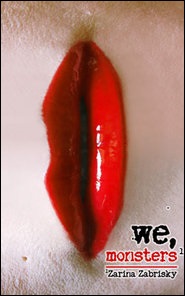

A Review of We, Monsters

by Zarina Zabrisky

Spencer Dew

A friend of mine recently reminded me why what Artaud did that day at the Sorbonne matters so much, not as some novelty of history, some anecdote of the zany past, something for a bio-pic that will one day disappoint us, but why it matters still, to us, now.

Fuck it, my friend said, and then he quoted Artaud, what Artaud said to Anais Nin in the wake of the reaction, the lack of understanding or attention, that his demonstration received: “They always want to hear about... I want to give them the experience itself, the plague itself, so they will be terrified, and awaken. I want to awaken them. They do not realize they are dead. Their death is total, like deafness, blindness. This is the agony I portrayed. Mine, yes, and everyone who is alive...”

Zarina Zabrisky knows some things about the theater, about the plague, the theatrical and the dead. One layer of fictionalization in her novel, a meta-voice, the narrator who hides in footnotes and an afterword, declares, “We, Monsters is a political manifesto.” What sort of politics? The politics of the bedroom? Sade is a presence here, to be sure, tattooed in abbreviated quotation on certain bodies, whipped or whipping, an inspiration, another level of narration, hidden in the shadows, offering his own take on human nature, on what is underneath the mask. Freudian politics? The repressed, returning, the desires shaped by society or slipping free from such constraints, stretching out without fetters in dreams and dungeons? Feminist politics? From sleepwalking through domestic routine, gender roles, to being on the receiving end of violent action and violent thought, lashing back, seizing control of the whip hand? Politics of exile, of dictatorial oppression? Here we have a character who used to fantasize that Lenin was her father, that finds herself in California but missing, always, Odessa, where the air “was like condensed sweetened milk: dense, alive. In the midst of a July night you could almost eat spoonfuls of air, and it would hit that sweet spot on the roof of your mouth. I’d searched for that lost taste ever since and never found it.”

My friend, pointing to Artaud exhibiting the plague, to an embodiment of the monstrous, the politics of performance, spoke also of mania and madness as necessary infusions of our work. Weaponize, he said, your artistic practice, your scholarship. By which he meant, in sharp part at least, and in echo of Artaud, “awaken them,” for they know not their own agony but shuffle on in numb denial.

Maybe I paraphrase, but it’s easy to get distracted with so much pain, so much play-acting. In this novel, there’s a man who pays women to pretend with him that he’s a tiny elf, that they feed him down shitty pipes, use his miniscule body to clean the filth from the sides of the hole. In the dungeon, arranging the ropes and chains, setting hooks into flesh or putting down the plastic to catch the golden shower, it is easy here to muse on theory, how Freud connected money to feces, how a fetish relates to a sublimated identity, how the dead aren’t in the past but always here in our present imaginings. Zabrisky’s protagonist exists in relation to various foils—a sister, maybe; dead relatives kindly and malignant, teaching tricks of mascara to keep her from crying or fingering under her skirt pleats while stinking of vodka and pickles; the johns with their peccadillos; a psychologist and his book. Mistress Rose (as assumed name, but is it less true than her name in the house, driving her bored kids home from school?) believes in one therapy above all others: “Book therapy was the only therapy that had ever worked for me.” Though by this she means, as I understand it, not merely distraction via reading, but fantasy writ large, the book of life, spread open, masturbatory daydreams of dinosaurs, distant dynasties, surreal blends of imagery, lusts and needs, raw force, the heat and flicker of life just beneath the skin.

Some days I was an Indian, a Pocahontas, lilies and eagle’s feathers in my braids, a necklace of tiger teeth and claws around my neck, a battle-axe in my hand. Other times I was Melpomene, the Goddess of Art, riding a black panther, a whip in my hand; and sometimes I was the Amazon Queen, my bronze legs gripping a pterodactyl’s flanks, its filmy back vibrating, pressed to my crotch. And sometimes, I would be all three, switching between one and another with the incoherence and inconsistency of a dream.

“Fantasy is reality,” she longs to say at one point in the text, speaking of literature, of art, “Reality is fantasy.” Which means, in part, that every face is a mask:

I saw myself: a flat paper face in the mirror. I wore my faces like masks. I had many masks. I had many women inside of me, dead and alive, and each me had her own mask—I didn’t know the woman in the mirror; that mask was new, scary. The cherry-red mouth on white skin, like a murdered body in the snow.

Her story is told through unfolding narrative but also the process of analysis, in scholarly apparatus, those footnotes, at once interruptions and augmentations, at times decorative like a heavy necklace at other times intrusive as a rape, ranting on about dissociative defense mechanisms, the roots of trauma. But ultimately, this is not a book about either murder or analysis, not about the rote realities of dominatrix work, but about what Freud offers in the manner of Artaud, an enactment, fairy tales as hyperbolic truths, nightmares as myths of origin, how we are—we are—ultimately what Zabrisky describes as “Torn pieces of thoughts, memories and fantasies floated through my mind . . . as if an invisible director was drunk and mixed up the pages of the script.” Fantasy is reality; reality is fantasy. What Freud offers us is not science but poetry, a weapon, a tool, for cracking open the question of “Why was I stuck in this body—and who was the person stuck in that body, anyway?”

Mistress Rose at first does not quite realize she is dead. And then she does, and there is agony, ecstasy, and enactment, “the experience itself, the plague itself.” Which we all need.

Official Numina Press Web Site