about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

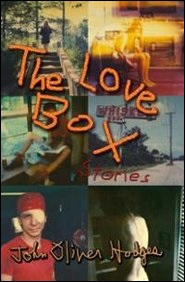

A Review of The Love Box

by John Oliver Hodges

Spencer Dew

“You obviously got some serious shit wrong with you, but I guess I shouldn’t complain” says one of the abusers in one of the stories in this collection. What he wants is to feel special, he just goes about it in an elaborate way, psychologically and physically degrading, brutal. Such is the world of The Love Box, where people use other people like dishrags, or worse, because people feel like dishrags, or worse. Abusers abuse and the abused take it. Degenerate artists sniff around for the raw material, people who disinter dead pets for their projects or stand above the naked body of a lover and imagine her posed as famous corpses in war atrocity photographs. One man has sex with a woman around the same time the undertaker is pumping her dead husband’s veins free of blood, “all that red syrup replaced with clear liquid,” and this is what he thinks about, as he fucks her. A woman is instructed to lie down naked in a pool of melted snow, and act like Ophelia, for photographs, which she does, despite the pain of the cold, maybe because she needs the money for chemical distractions to help her kill the time, but maybe also just to kill the time. When innocence springs up, it does so like mushrooms in the general thick mess, like those two young girls wearing plastic body suits of murdered children, sitting in the graveyard on Halloween gorging on stolen candy. Meanwhile, people watch from their stoops or from behind blinds, listen through the walls.

But Hodges is interested in a particular form of violation. Consider this exchange:

Every girl has nipples that beg, Bull goes in the sexy voice he saves for when we are alone. You are a girl, he goes. Therefore your nipples beg.

Bull fondles me.

No, Bull, I go.

Open your mouth, Bull goes.

What?

Bull presses down with his fingers, pinching me, and he pulls me close to him.

I open my mouth.

The most beautiful mouth in the world, Bull goes, and lets me go.

The satisfaction there, the prize, is in the instant, the compliance, which gets followed fast by disregard; proof of ownership, then the smugness of abandonment. This is the dynamic of collection; as surely as the character in one memorable story here collects scabs, this abuser is collecting instances of submission, moments of complete control. Where Hodges sees a parallel to this is in photography, which, in these pages, is likewise a violation, not only an invasion but a seizure of intimacy, taking—as we say—pictures. While simultaneously taking refuge behind the mask of the device; looking “at the world through glass,” as one photographer has it, rather than face-to-face. “I’m an eyeball. Eyeballs don’t think. I’m a watcher, a looker, a recorder, a witness, and this, I know, somehow, is important,” he narrates (rationalizes?) as he snaps photographs of an attempted rape.

Photography of human subjects becomes another arena for dominant/submissive desires to play out. The female nude becomes a thing; the artist, behind his glass, “warping it out of shape, objectifying it, animalizing it, exploding it into nature.” Female bodies get dragged down to the level of manikins, corpses, and in light of this theme the girls in the graveyard, pulling their rubbed suits down to expose their breasts, chomping Butterfingers and thinking about ancestor worship, appear in an even spookier light.

Photography becomes the extension of sadism, the next stage. One abuser asks a woman to wash the dishes naked, then orders her to “Pretend like you wiped your ass but forgot to pull away the paper,” to stand with toilet paper hanging from your ass. “Stop looking so fucking intelligent,” he says next, and then the pain begins in earnest. But all this theatrical effort is nothing compared to what the photographers do, either by simply walking into a house and taking pictures of a poor woman and her children or posing a body, arranging and manipulating it, asking for certain psychological responses. Act like you have killed someone, for instance, which is in many ways a cleaner and more ingenious prompt that asking for someone to really inflict pain upon themselves.

“I’ll have to arrange her hands in the correct manner,” says one photographer. “Everyone will get the reference.” But the reference, ultimately, is not to any one historical scene as much as it is to ownership, control, the photographer not as one who documents God—which is something one of them says—but one who acts as God. And while the girls in this book are, as one character puts it, good at nodding their heads, submitting and saying yes, they are also not unaware. One notes, of her current lover, that “behind his fake abuse of me . . . a raging desire to hurt me, a desire that, should it break the surface of his unconscious, would be indifferent to any consequences that might result from being cruel.” And recognition of that is essential, as essential as initial resistance and as essential as an ultimate brokenness, standing there with an open mouth no longer needed. With photography, the moment lasts forever, is captured and printed, reproduced, blown wide: the most beautiful mouth in the world, thinks the artist, because it is all mine.

Plenty more goes on in this carnival of a book, but the way authoritarian abuse slides so easily into the art of photography shows you something about how Hodges stitches together themes, tones, ideas, and incidents, constructing something you can’t easily step away from or leave behind, escape or forget.

Official Livingston Press Web Site