about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

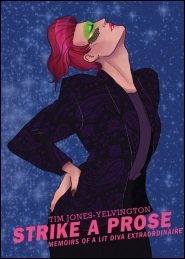

A Review of Strike a Prose:

Memoirs of a Lit Diva Extraordinaire

by Tim Jones-Yelvington

Spencer Dew

After the death of the author came the rise of the reality television star. True, these moments were part of a longer trajectory of media innovations and practices—from mass-produced woodcuts of Martin Luther’s face in lieu of vernacular Bibles, the factory films of Andy Warhol transforming excruciating focus into an avenue of transcendence, the global proliferation of corporate icons communicating brand identity beyond words, plus the pontification of all those postmodern theorists on how the self was something fluid and fractured and always contingent. There was the trickle-down era of the supermodel and the celebrity athlete, following fast on the path laid out by the aviatress and the explorer, linking stardom with grace and skill and daring. Then came our era, where the celebrity as the focus of fascination hinged on a mix, simultaneously, of schadenfreude with an unlikely aspirationalism: those “real” housewives and weight loss champions, teen mothers and trash talkers, those half-naked maroons and harried apprentices, those competitive romancers and exceptionally everyday people under the scrutiny of a surveillance that would turn them into something superhuman. Let me put it plain: they became our gods, and the canniest among them knew it. To be such a star meant that one could “do anything,” “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody” and the act would only help your ratings, which is contemporary shorthand for adoration. Grab the world by its most intimate bits, then boast of your predation, jet around in your personal gold-plated plane gorging on franchise fried chicken: humanity has evolved into pure brand, into character no longer bound by the laws of nature or facts, into a plot device manipulating anxiety and paranoia via social media feed. Celebrity, in this new and apocalyptic-feeling age, is revolutionary, but the most obvious revolutions produced by and through it are authoritarian ones. In matching hats, chanting, the masses seek unity with their idol, the star as populist deity, experience of his stardom an effervescent event, a mystical communion wherein the identity and potential of his fans were defined by the object of their devotion. This, as the producers of reality programming might wryly observer, is our reality: celebrity has weaponized itself. We, the people, are in trouble, and we love it; we’re addicted—celebrity-struck and star-fucked.

Tim Jones-Yelvington, who in the indie lit scene of the 1990s developed a performance persona—part drag, with its incumbent campiness; part masking in that bare-faced sense of Mardi Gras Indians, a revelation of a deeper and broader truth of being, beyond the individual instantiating it—here reflects (fictionalizes, theorizes, appropriates and riffs on, “tranes” in the way Coltrane made old tunes remarkably new and inimitably his own) on that work, that performance. In keeping with the inherent element of camp, there is a kind of double consciousness, an awareness of the phenomenon from inside and out, which, here, fuels an ambivalence about the celebrity culture and its mechanisms. Jones-Yelvington celebrates the world-changing power of sequins while recognizing that the world requires changing. Strike a Prose has beatings and bullying at its margins, abuse and exclusion, a wariness about the ways carnivalesque irruptions serve to reinforce the normalcy and authority of the status quo, the ways drag’s disruptions of and self-conscious parody of the gender stereotypes may reiterate such stereotypes. Present throughout this text is the threat—the inevitability—of the “#fagaclysm,” an eschatological and epistemological event, the end of a world and the eclipse of a certain stance or pose in relation to that world, what happens when relations stop being ironic and start getting real. As Jones-Yelvington puts it here, “If you’re trapped in the dream of sequins, you’re fucked.”

Transgression can only ever be a step, and as each step beyond changes the borders of where and what that beyond is, transgression sets new boundaries just as revolutions start new regimes, new oppressions. What Jones-Yelvington is interested in—and what his character, TJY, lit diva extraordinaire, celebrates and strives for—is that excess (“Splurge”) that “Rupture” that breaks the bounds of form and limits. Once done, it must be outdone—one always risks getting trapped in the dream of sequins. When TJY’s mode of performance works, the separation between self and world is tossed away; the body “is not a closed, complete unit; it is unfinished, outgrows itself, transgresses its own limits.” The sequins affixed to one’s face glitter like miraculous merman scales; a fantastic transmogrification has been effected. When it doesn’t succeed at transgression, when it becomes rote, expected, the act of embodying the attitude of a diva is described here as an addiction, sequin abuse. “I lit sequins on fire and inhaled the flames. I chopped sequins into a fine powder I insufflated through a rolled rejection slip. I tied off my upper arm with a feather boa and injected sequins in my bloodstream.” The “I” here is revealing, for the performance TJY seeks (and Jones-Yelvington theorizes) is one of transgressing and transcending the self: “the diva, having become alter ego, drops, so that I do not disappear, but find in that sublime sequins a forfeited existence.” Or to put it another way: “TIM JONES-YELVINGTON IS NOT A PERSON!” This declaration, delivered with the force of manifesto, circumvents the risks (the trap, the habit) of confusing the performance of a diva with neoliberal individualism. This is the difference between mystic and mere celebrity, between event and ego. And for Jones-Yelvington it represents the essential loophole that can save stardom from being something oppressive, by making it not about an individual but a potentiality for all. The diva is the audience’s magic mirror, or, to cut to the core of this book: “TIM JONES-YELVINGTON IS A VERB!” “TO TIM JONES-YELVINGTON IS TO PICK YOURSELF UP, BRUSH THE DUST FROM YOUR TEMPLES, SPONGE AWAY THE BLOOD, AND SPANGLE YOUR BRUISES WITH MOTHERFUCKING SEQUINS!”

To pull the threat of tension central to this book, it’s worth observing that Donald J. Trump is a verb, too, another magic mirror, another mask perceived by his legions of fans as a face that can be assumed, a source of power, permissibility. To Donald J. Trump is to bully and hate-monger liberated from social constraints. There are no sequins, per se, to this bland form of drag, but what bruises and fears are covered over by the red hats, dispelled by the tiki torches, the rhythmic call for the imprisonment or deportation of various bugbears invented for such therapeutic purposes. In Strike a Prose, there’s a scene of triumph as a TJY fanboy, marginalized in the world of cruel youth, finds himself in a compromising position and yet liberates himself, painting his face with his own shit, transforming into something fierce, transcendent of limits and shame and anxiety, merging with the idea of the diva to rise, to triumph. But can’t the same salvation through the performative, through identification with celebrity and its dazzling masks, occur for that boy’s bullies and mockers, too? There’s a threat of taking the shimmer of the sequins as substance, to be sure, but there’s a wider threat, playing like an ominous background beat throughout this book, of the world itself, so full of people so full of viciousness. At one point our protagonist muses, “But whatever, it hasn’t been so bad, making art in the ruins . . . The only sucky part’s the hunger, the constant violence.” How like a diva to toss that off, lightly; how like a diva, too, to call our attention back to it, framing the phrase in invisible inverted quotes but framing it nonetheless. The constant violence. Celebrity promises pathways of temporary escape from it—prancing and voguing, sashaying and slaying—but these very dynamics of celebrity, these transgressive salves, are also structurally bound in and even supportive of the larger system of oppression. To embrace the pose of a diva can be precisely the revolution you need, but it is never revolution enough. This tension, reconsidered again and again throughout this book—in faux interviews with Terry Gross, in audacious statements about the responsibilities of celebrities and their anointed role as social saviors, in spun and self-imploding routines about and exemplifying the feel and transient flare of performance itself—is never sutured or solved, but left gaping, like that “most erotic portion of a body where sequins gape,” a riddle to be pondered after the show is done and the curtain drops. But until then, we’re blinded by the starlight, the raw wattage of TJY:

Lit up, I traipsed, a dear, yummy elf. I delegated my secretions. I curved my syntax. I applied a retro astringent. While ordinary readers wore T-shirts, I flared my tacky claws. A despot, depositing bon mots. The people called, Let him rape us! Baby, I had clout.

These “memoirs,” despite (or it is because of?) such pyrotechnic provocations on performance, can read at times like a farewell to performance. If not swan song, this book surely signals a transition, a new epoch for Jones-Yelvington (who, outside of his diva persona is an educator and activist as well as writer and poet) and his persona. This text is its own “#fagaclysm,” the climax and reimagining of TJY as celebrity and Jones-Yelvington’s fabulous revels in and critical reflections on the phenomenon of celebrity.

Official Tim Jones-Yelvington Web Site

Official co•im•press Web Site