about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

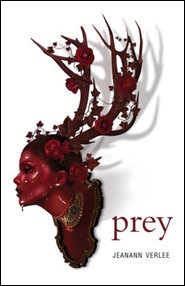

A Review of prey

by Jeanann Verlee

Spencer Dew

Flecks of spittle fly from the mouth of the man on the television, the accused, now overflowing with accusations of his own, roaring, teeth bared below his predatory eyes. I am thinking of a particular man, but he is, ultimately, merely one in a seemingly endless menagerie, snarling with the same contempt, the same sense of invulnerability, the same entitled swagger. He punctuates the air with a pointed finger, a suggestion of violence. This is what it means, for him, to be a man, and that meaning has been challenged. Rape culture, provoked, rises to defend itself.

We hear such roars throughout this book, a collection of poems that are often wrenching, dripping with threat and fear and the clenched jaw of a survivor testifying, telling her story. Yet Verlee offers us voices and valences of both those who endure and those who inflict cruelty and horror. Some pieces here have been assembled in part from police reports, court documents, text messages bragging of assaults, media coverage of trials and acquittals. We hear men roughly grabbing the discourse, the conversation, even the role of victim; men, acting like ownership is the only mode of engagement with the world. Masculinity, for such men, is modelled on ownership, domination—from the global conquest and pillage of colonialism to more intimate cruelty, more immediate forms of abuse. We hear such men polishing their weapons—“Buff, stroke, clean. / Such dreadful worship. / More tenderness for the killing machine / than those who will die.” And we hear the mansplaining and obliviousness of men basking in their “means, male and white,” assuring themselves that, “They don’t mind,” or reflecting with vague bafflement that she “wouldn’t even slap me.” The sense, reading this book, is similar to that of strolling through a museum’s taxidermy halls, the eyes of bears and big cats uncanny in their unconscious effect. The world Verlee gives us is not a safe place, and it is undeniably our world, over and over again.

There are poems here, too, that directly channel the throb and pant of fear, as in the singular focus of the haunting “Pack Hunt,” which alternates rational statements on the page’s left hand side—counting teeth in one’s mouth, or replaying good memories, or enduring another slap, or planning to race for a gun—with each of them crossed out, not erased but rendered moot, pierced, with the italicized pleading on the page’s right hand side, variations on a single, simple, desperate theme: “Please, just don’t hurt my dog.”

Animals populate these poems in darker ways, as models of predation, natural examples of cruelty or endurance. Voices speak to us from inside the mouths of various creatures, selected for the way their behavior sheds some light on the ways of human men and women. Certain snakes, we’re told, begin digestion even before swallowing their prey; sharks frequently lose teeth in the flesh of the animals they bite; coyotes mate for life. Recourse to these creatures naturalizes the abuses described in the book: there’s a bludgeoning sense, here, that culture has sprung up around some primal impulse, a need for meat transmuted, through the curse of civilization, to a need for conquest, for exploitation. The skill of the hunt sublimated to the domestic backhand, as in a poem about a mother, whose hand goes from “wrist-deep in the raw mash / of meat, egg, catsup, watered bread; // the whole-hand crush of canned tomatoes; / petite fork-whisk of powdered sugar into milk” to striking her child with “Such precision, even in beer-battered rage.”

Other pieces celebrate the smallest of survivals, even such survival involves selling off of oneself or learning to die and die again. There is a necessary, tonic, strength throughout, less in the suggestion of vengeance—though there is at least one glimpse of an apron splattered in what may or may not be red wine—than in the growth of a certain armor, like a crocodile’s skin. The narrator of one short poem starts “wearing sports bras to sleep,” a kind of metamorphosis, more compact, ready to spring, to flee, to fight. Another, asked to reenact scenes from her abuse before a courtroom—“Hold the knife / the way he held it. // Say the words / the way he spoke.”—clenches her own life defiantly. When her abuser makes parole and the police urge her to “move away,” she, instead, opens her window, waiting, not prey but a trap, not a victim but a woman smelling the fresh air and waiting, ready. Reading this collection, one cannot be apprehensive for her but one also cannot but applaud her. Verlee gives us a world of teeth and claws: there is no option but to bare one’s own, stand one’s ground, snarl back, live on.

Official Jeanann Verlee Web Site

Official Black Lawrence Press Web Site